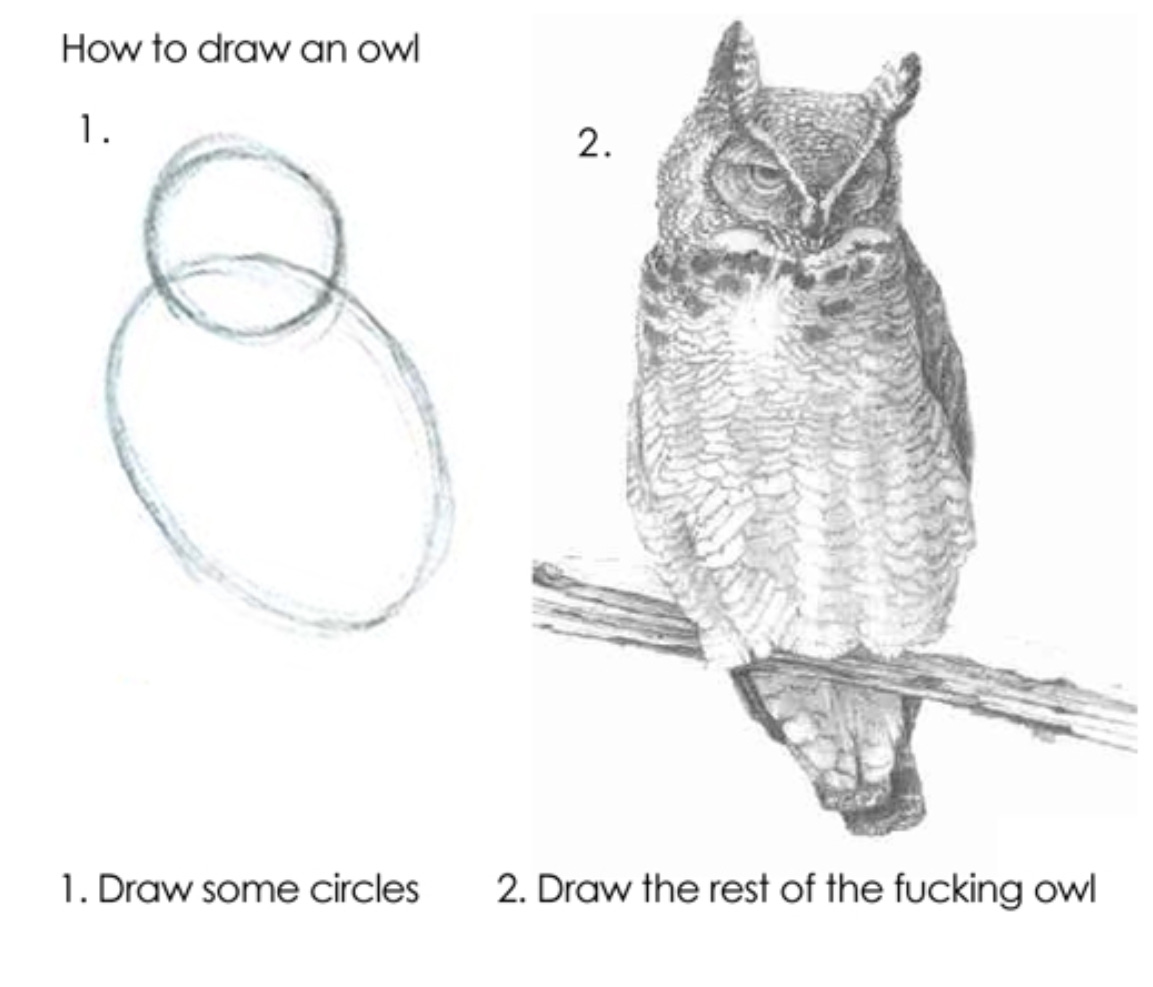

Drawing the rest of the owl

Anyone who has designed an API knows the tension between keeping it simple and making it work out of the box for as many use cases as possible.

With S2, we've tried to keep the core data plane API as simple as possible. This is deliberate – we're trying to be a new type of storage primitive, and a big part of that is being clear about the interface and therefore which guarantees you can and cannot expect from S2.

We feel that some functionality is best left to users. But I can see how this sounds a bit like learning how to draw an owl:

To help bridge the gap, I want to explore some patterns for dealing with complexities that may come up when building systems around S2.

S2's data plane

To start, let's first consider what S2 gives you. The central data structure is a stream: an append-only sequence of records. S2 makes streams durable.

If you have not seen S2 before, the concepts documentation walks through basins, streams, and records in more detail.

Records in S2 are immutable and receive a sequence number expressing their ordering within the stream. Streams can be bottomless – they can grow indefinitely in size – or can be trimmed explicitly or based on TTLs.

All appends to a stream are fully durable on object storage before acknowledgement, and writers can coordinate with concurrency controls.

What functionality is missing?

Schemas and typing

Records in S2 are a very minimalistic abstraction. A record has a sequence number, a timestamp, optional key-value headers, and a binary body. S2 is entirely agnostic about what you store in those headers and body.1

const s2 = new S2({

accessToken: process.env.S2_ACCESS_TOKEN!,

});

const stream = s2.basin('my-basin').stream('my-stream');

const session = await stream.appendSession();

// Append a single record.

const ack1 = await session.submit([AppendRecord.make('record 1')]);This just means that you need to bring your own serialization and deserialization logic for appending to and reading from S2 streams. S2 only speaks bytes. There are many ways of doing this, as we will see.

Here, S2 and AppendRecord come from the TypeScript SDK (@s2-dev/streamstore).

Large messages

Depending on the type of data you are serializing, you may run into another limit: the maximum size of a record on S2 is 1MiB.

This is big enough to not be a concern for many use cases, but it adds complexity. Maybe you are storing messages from an AI assistant, for instance – typically these are tokens, but occasionally they might be entire files, or images, or audio clips, which could easily exceed 1MiB. What to do?

There are two general approaches for dealing with this:

You can store a pointer to the data. Instead of putting the image in an S2 record, you could store a URL to an S3 object or similar. The advantage to this is that your data can still be represented by a single message. The downside is that now there is another service in the mix, which also has to be accessible both by your stream writer and any readers.

Alternatively, you can implement a framing scheme, and essentially spread your data across multiple records. S2 can continue to be the single source of data for your application, but there's the complexity of implementing framing logic, which will also need to be resilient to failures.

Duplicates from retries

S2's SDKs provide transparent retry logic for transient failures. But, this gets tricky with datastores.

What happens if you retry an append which failed in an "indefinite" way – for example, due to a network timeout? Perhaps your original attempt did succeed, even though the call ultimately failed. Retrying this append would therefore result in record duplication on the stream.

For some applications, the possibility of duplication is acceptable. For others, it's not. This can be particularly treacherous if you are framing large messages over multiple records! What options do we have?

Well, you could simply not retry any failed appends. The SDKs specifically allow you to configure whether or not to retry appends. But then it shifts the burden onto the user for inspecting if their prior attempt succeeded or not.

You could use match_seq_num as a concurrency control. This is the S2 equivalent of a CAS operation. This works, though it again throws retries back to the writer.

Alternatively, you could inject data that allows readers to perform deduplication. This can be the simplest option, as it allows you to configure the SDK to retry as much as it wants. If duplicate records are stored on the stream, readers can disambiguate them by inspecting the data.

Patterns for dealing with these issues

We want a strongly typed S2 client. We want to be able to store large messages safely. And we want to avoid duplicate records while still allowing retries for the smoothest possible user experience.

There are many ways of accomplishing this. Here's one! We will start in reverse.

Dealing with duplicates

Duplicates are fine so long as any reader of our stream can identify and remove them. A simple and efficient way of doing this is simply for the stream writer to include an idempotency key.

A really simple key could just be a writer-assigned index, stored in a header.

From the perspective of the stream writer, this would look like:

{ "headers": [["_index", "0"]], "body": "Hello" }

{ "headers": [["_index", "1"]], "body": "world!" }If a retry occurs, it would be possible for a reader to see a duplicate:

{ "headers": [["_index", "0"]], "body": "Hello" }

{ "headers": [["_index", "0"]], "body": "Hello" }

{ "headers": [["_index", "1"]], "body": "world!" }In the reader code, we just need a filter. It can increment its internal counter every time it sees a new record with a higher index. If it ever sees a record with the same or lower index, it can assume it's a duplicate, and simply ignore it.

What if a writer crashes entirely and needs to append to the same stream though? Or if there are multiple writers? We need an extra bit of information to identify the writer, such as a UUID.

{ "headers": [["_writer", "x-B1At9xVppm"], ["_index", "0"]], "body": "Hello" }

{ "headers": [["_writer", "x-B1At9xVppm"], ["_index", "0"]], "body": "Hello" }

{ "headers": [["_writer", "x-B1At9xVppm"], ["_index", "1"]], "body": "world!" }

{ "headers": [["_writer", "uSEFRpXqIldw"], ["_index", "0"]], "body": "How cool." }Using an idempotency key like this allows the reader to reconstruct the actual flow of records, even across retries and writer crashes: ["Hello", "world!", "How cool."]. With both _writer and _index present, the reader just keeps track of the highest _index it has seen for each _writer, and drops any record whose _index is not greater than that per-writer maximum.

In the TypeScript patterns library (@s2-dev/streamstore-patterns), this idea shows up as _dedupe_seq and _writer_id headers added to each record, and a DedupeFilter that drops duplicates based on that pair.

Storing large messages

With the dedupe strategy, readers can confidently reassemble the exact sequence of messages that were appended, even if the appender experienced failures and generated duplicate records.

Similarly, writers and readers can co-operate to store large messages over multiple records. This is "framing" generally. Again, many ways of doing this, but a simple one is to use a framing header.

When a stream writer appends a message larger than 1MiB, it can split it into multiple <= 1MiB records, and include headers for bookkeeping. In our example implementation, whenever we map a message into multiple records, we inject headers on the first record to capture the total number of records that make up the message, plus the size in bytes of the payload.

Readers can consume the stream, and start assembling a new message whenever they see these frame headers. The size hint can be used for allocating a buffer, and also for detecting truncation.

Truncation might happen if the stream writer crashes before it completes sending all of the records comprising a full framed message – it is fair to simply ignore any messages that can't be completely reassembled.

This is a very simple framing scheme, but it's a good starting point. If you plan to have multiple concurrent writers to the same stream, you'll need to add additional logic for parsing interleaved messages – but for single writer / multiple reader architectures, this works well.

Strong types

If our stream writer and readers are collaborating to dedupe any repeats, and to frame large messages, then it's pretty simple to add support for strong types. We just need some way for our type to be serialized to bytes (for the appender), and be deserialized from bytes (for the reader).

If you are working with largely textual data, this could just be JSON. You could also use binary formats like MessagePack or Protocol Buffers. Anything works!

Putting it together in TypeScript

To make this a bit more concrete, here is a small example that combines all three ideas — strong typing, framing for large messages, and deduplication — using the helpers in @s2-dev/streamstore-patterns.

While the examples here are in TypeScript, the patterns themselves are S2-level ideas. You can apply the same approach with any of the S2 SDKs or even directly against the REST API by managing framing headers and dedupe keys yourself.

First, we define a multimodal message type and a ChatMessage that wraps it. This is the message type we want stored in our stream.

import { S2 } from '@s2-dev/streamstore';

import { serialization } from '@s2-dev/streamstore-patterns';

import { encode, decode } from '@msgpack/msgpack';

type MultimodalMessage =

| { type: 'text'; content: string }

| { type: 'code'; language: string; snippet: string }

| { type: 'image'; bytes: Uint8Array };

type ChatMessage = {

userId: string;

message: MultimodalMessage;

};Now we can write messages to an S2 stream. The SerializingAppendSession will take care of serializing to bytes, splitting large payloads into frames, and tagging each record with a dedupe sequence so retries are safe:

async function writeMultimodalConversation() {

const s2 = new S2({ accessToken: process.env.S2_ACCESS_TOKEN! });

const stream = s2.basin('my-basin').stream('my-stream');

const appendSession = new serialization.SerializingAppendSession<ChatMessage>(

await stream.appendSession(),

(msg) => encode(msg),

{ dedupeSeq: 0n }

);

await appendSession.submit({

userId: 'alice',

message: { type: 'text', content: 'hello world' },

});

await appendSession.submit({

userId: 'alice',

message: {

type: 'image',

// Imagine this is a large screenshot or image; the patterns

// helpers will automatically frame it across multiple records.

bytes: new Uint8Array(5 * 1024 * 1024),

},

});

}On the read side, DeserializingReadSession will dedupe, reassemble frames into full payloads, and hand you back strongly-typed ChatMessage values that you can branch on:

async function readMultimodalConversation() {

const s2 = new S2({ accessToken: process.env.S2_ACCESS_TOKEN! });

const stream = s2.basin('my-basin').stream('my-stream');

const readSession = new serialization.DeserializingReadSession<ChatMessage>(

await stream.readSession({ tail_offset: 0, as: 'bytes' }),

(bytes) => decode(bytes) as ChatMessage

);

for await (const msg of readSession) {

switch (msg.message.type) {

case 'text':

console.log(`[${msg.userId}] ${msg.message.content}`);

break;

case 'code':

console.log(

`[${msg.userId}] (${msg.message.language} code) ${msg.message.snippet}`

);

break;

case 'image':

console.log(

`[${msg.userId}] <image bytes=${msg.message.bytes.byteLength}>`

);

break;

}

}

}You can derive your own patterns from here: for example, using different streams per conversation, or layering your own schema/versioning metadata on top of the framed messages.

Conclusion

You can find a SerializingAppendSession<Message> and DeserializingReadSession<Message> in TypeScript that implement the strategies discussed above in the @s2-dev/streamstore-patterns package.

We've just scratched the surface of what's possible to build on top of S2. If you have a use case that doesn't fit nicely into the pattern above, reach out and we would be happy to help see if S2 might still be a good fit.

Footnotes

-

Almost entirely. Technically, command records use a reserved shape, described in more detail in the command records documentation. ↩